¡Co-existimos!

A multi-species inquiry into morpho butterflies as urban companion species

Melina Campos Ortiz

PhD Student in Social and Cultural Analysis

Concordia University

Montreal, Canada

melinacampos@gmail.com

Introduction

“See the borboletas de verão caught in time and space like mini UFOs, just visiting, just stopping by, entering our lives, transforming everything just for a moment, showing us a glimmer of a different world, then passing on?” (Raffles, 2010, pp. 13-14)

In December 2020, while returning from the farmers market on a Saturday morning, I encountered a morpho butterfly on a street corner in San José, Costa Rica. Morpho butterflies are among the biggest butterflies globally (Rain Forest Alliance, 2012) and are well known for their spectacularity. For instance, The Encyclopedia of Rainforests describes them as follows:

“Morpho peleides is a spectacular butterfly found from Mexico to Colombia. The underside of their wings is drab, but the topside is an iridescent blue. With their slow, loping flights, they look like large, flashing, azure sequins zigzagging against the green fabric of the forest. Their radian display may be a defense mechanism-so much flash and dazzle makes it difficult for predators to get a lock on their target.” (Jukofsky, 2002, p. 72)

Despite their magnificent and radiant blue wings, they are rather difficult to see even in the forests. That is why some cultures, as the Maleku in the northern plains of Costa Rica, consider them as a sign of peace and good luck (Maleku EM, 2015). I have been lucky enough to see many of them in the forests, mainly in natural reserves and national parks in Costa Rica. I have always feel reassured by their presence. But a morpho butterfly on my street? My first impression was not of reassurance by estrangement. I was almost sure she escaped the butterfly garden from the University of Costa Rica, located not far from where I lived. There was no other explanation for her presence on a concrete and asphalt milieu. And then I thought, why cannot morpho butterflies inhabit San José?

While a simple answer would be that their habitat is fragmented and human beings directly threaten this spectacular butterfly because of their beauty (Rain Forest Alliance, 2012), my query was more profound. Escobar (2019) gave me one answer:

“Earth has been banished from the city. By “Earth,” I mean–based on indigenous cosmovisions as much as on insights from contemporary biological and social theory—the radical interdependence of everything that exists, the indubitable fact that everything exists because everything else does, that nothing preexists the relations that constitute it.” (p.132, emphasis added)

But also more questions.

Archambeault (2016) suggests that “an encounter, a meeting with someone or with something, is affective when it triggers some sort of effect; when it inspires, unsettles, troubles, moves, arouses, motivates, and/or impresses (p. 249). I was intrigued and troubled by this unsettling encounter, asking myself if it is possible to imagine a different city, one in which an encounter with morpho butterflies would generate reassurance and no awkwardness.

Inspired by the methodology of imaginative ethnography as displayed in A Different Kind of Ethnography (Culhane and Elliot, 2017), I engage in a series of photo walks as a way to slow down and pay attention to morpho butterflies as urban dwellers. While I had many questions in mind, I stick to two: What can a photo-walk reveal about human and morpho butterflies entanglements in the urban space? Can photography help us to re-imagine such relation and bring Earth back to the city?

In the following pages, I will present some of the findings of this exploratory exercise. I will first introduce the inquiry mode I followed, which combines multimodal (Culhane and Elliot, 2017) and multi-species ethnography (Kirksey and Helmreich, 2010). Then, I will present some of the photos that came out of my walks in the form of a small photo essay. Drawing on Raffles (2001, 2010), van Dooren (forthcoming) and Demos (2017), I will briefly explain how they denote that the modernist nature/culture divide is very much alive in San José. Finally, I will show some ideas for an activist intervention inspired by the work of Haraway (2006), Gibson et al. (2005), and Escobar (2019) that aims to re-imagine such relation. This exercise does not intend to be exhaustive or conclusive. On the contrary, it seeks to explore new creative ways to promote co-habitation in what Franklin (2017) has called “the more-than-human city.”

1. Insects and walks: A multi-species and multimodal inquiry

“[B]eing and moving through space helps us construct our identities for ourselves and for others, and to claim, literally and metaphorically, a space in the world.” (Moretti, 2017, p. 97)

Hugh Raffles (2010) starts his Insectopedia with a provocation:

“Imagine an insect. What comes to mind? A housefly? A dragonfly? A bumblebee? A parasitic wasp? A gnat? A mosquito? A bombardier beetle? A rhinoceros beetle? A morpho butterfly? A death’s-head moth? A praying mantis? A stick insect? A caterpillar? Such varied beings, so different from each other and from us. So prosaic and so exotic, so tiny and so huge, so social and so solitary, so expressive and so inscrutable, so generative and so opaque, so seductive yet so unsettling. Pollinators, pests, disease vectors, decomposers, laboratory animals, prime objects of scientific attention, experimentation, and intervention. The stuff of dreams and nightmares. The stuff of economy and culture. Not just deeply present in the world but deeply there, creating it, too.”(Raffles, 2010, p. 3, emphasis added)

Like him, I am interested in exploring how morpho butterflies have become “the stuff of dreams and nightmares and “the stuff of economy and culture” (Raffles, 2010, p. 3) in the city I inhabit.

Multi-species ethnographers, as Raffles (and others such as Tsing, 2010 and Kohn, 2013), are studying how “a multitude of organisms’ livelihoods shape and are shaped by political, economic, and cultural forces” (Kirksey and Helmreich, 2010, p. 545). They pay attention to how non-human others are “not just deeply present in the world but deeply there, creating it, too,” as Raffles (2010) beautifully reminds us. As Kirksey and Helmreich (2010) suggest, multi-species ethnographers are engaging in “bicultural hope by practicing “an anthropology that is not just confined to the human but is concerned with the effects of our entanglements with other kinds of living selves” (Kohn, 2007, quoted in Kirksey and Helmreich 2010, p.545).

While, as Hartigan (2015) points out, emergent multi-species ethnographic projects tended to focus on “non-human domains” such as jungles and forests, exciting multi-species ethnographic projects are now taking place in “human dominated” spaces. Such is the case of Feral Atlas (Tsing et al., 2020), a comprehensive multimodal project, curated among others by Anna Tsing and Jennifer Deger, that explores “the ecological worlds created when non-human entities become tangled up with human infrastructure projects.” Multi-species thinking has permeated other fields such as urban planning (e.g., Franklin, 2017; Houston et al., 2018) and has definitely arrived at the city.

To immerse me in the lives of morpho butterflies as urban dwellers, I decided to explore walking and recording as world-making practices. As Moretti (2017) argues, “as a way of inhabiting, researching, and representing everyday realities, walking is an imaginative practice (p. 93). According to the author, walking allows us to think about, construct and co-create spaces. It also allowed me to try to understand what was I was looking for. I only had two specific destinations in my walking journeys: the butterfly garden at the University of Costa Rica and the butterfly garden at the Museo Nacional de Costa Rica. Walking between the two sites does not take more than an hour. However, in several detours between those two spaces, I realized that while seeing a morpho flying across the city is almost impossible, those magnificent butterflies are present in the city imaginaries.

Following Boudreault-Fournier (2017), who suggests that we can use recording devices “to creatively and imaginatively relate with the various environments in which we conduct research” (p. 70). I decided to use photography to record “my findings” and showcase those imaginaries. In this case, I don’t intend to prove a hypothesis. On the contrary, following Ware (2011), I am drawing on photography’s visual potential to pose questions. My ultimate goal is to “create an opening for dialogue, a space in which to contemplate the state of our lives and our culture” (Ware, 2011, p.11) in the urban space.

2. Morpho imaginaries in the city: A photo essay

“The exile of Earth from the city is a reflection of a twofold civilizational anomaly: on the one hand, the construction of cities on the basis of their separation from the non-human living world…” (Escobar, 2019, p. 132, emphasis added)

I made at least six walks at the University of Costa Rica and San José city center to produce this photo essay. I took several pictures, and I kept five of them that denote how morpho butterflies, while not being official inhabitants of the city, are present in different spaces in the city. The suspected areas for them are butterfly gardens. But they are also present in museums, gift shops, and even in Costa Rica’s highest denomination banknote.

This photograph depicts a botanical garden located at the University of Costa Rica main campus, where I suspect morpho butterflies inhabit. In my six years as a student on such a campus and a lifetime of walking there, I have never seen anyone coming in or out of it. It feels as if someone threw away the key for the lock. I called it “exclosure,” inspired by van Dooren (forthcoming), who shows the conservation approach to keep animals in and keep human beings out and other predators out. While I celebrate such sanctuaries, it makes me sad that butterflies are welcome in the city only in the spaces where we are not.

This photograph shows the entry to the University of Costa Rica butterfly garden managed by the school of biology as a scientific space. It is possible to read that entrance to the area is limited to some hours a day in the sign. This space represents an enclosure, as different butterfly species are allowed to live there but not getting out. While studying butterflies is fundamental for their conservation, butterflies here are not free, but as Raffles (2010) puts it in his provocation quoted above: “prime objects of scientific attention, experimentation, and intervention (p.3).

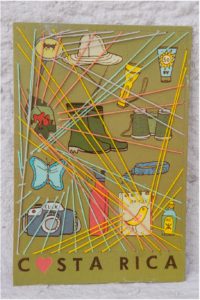

Wandering around in the city on a Saturday afternoon, I entered Hola Lola’s, one of Costa Rica’s most popular illustrators, new gift shop space. Thinking about butterflies, a set of postcards about “biological diversity” aimed at tourists called my attention. They try to convey the “rainforest experience” as spaces where encounters with strange and magnificent creatures such morpho butterflies are mediated by magnifying glasses, binoculars, and all sorts of adventure gear. These postcards are reminiscent of “Victorian traveling science”, or as Raffles (2001) puts it:

“Biological diversity makes conceptual sense only in the context of those specific epistemological frameworks that turn a particular nature into an object of inquiry, and Victorian naturalists (among others) were actively engaged in ensuring that plants and animals came to be understood in such terms.” (p. 514)

After some weeks of thinking about morpho butterflies, I felt the need to encounter them. I knew the only place where I would find them for sure in San José was at the Costa Rica National Museum’s butterfly garden. Entering the site, I felt refreshed. All in all, it is one of the few green havens in the city. At the same time, I did not feel the reassurance that I feel when I encounter a morpho in the forest. Getting there, I know what to expect. Reading through the work on Debora Bird Rose, I realized that butterfly gardens cancel mystery, and as she reminds us: Mystery signals the complexity and integrity of our world. A system that is entirely knowable is a dead or dying one: “total predictability would signal crisis—loss of connection” (Rose, 2005, quoted in van Doreen, forthcoming).

While I can be critical of butterfly gardens as victorian science legacy spaces where the connection is lost, I cannot resist its sensorial cues. The last photo -or set of images- of this essay, by far my favorite, shows that despite all:

“We simply cannot find ourselves in these creatures. The more we look, the less we know. They are not like us. They do not respond to acts of love or mercy or remorse. It is worse than indifference. It is a deep, dead space without reciprocity, recognition, or redemption.” (Raffles, 2010, p. 44)

The fact that taking a picture of a butterfly flying that conveyed such feeling was a real challenge made me reflect on Raffles’s proposition that “the more we look, the less we know.” I want to believe that that might be the secret to keep Rose’s mystery somehow alive inside these enclosure spaces, that despite all I get to enjoy.

Summing up, the five photos that compose this photo essay denote how the nature/current divide is very much alive in San José. Drawing on Serres, Demos (2017) suggests that the root of the current environmental crisis is Cartesian dualism, which posits human beings as the subjects of the world while relegating everything else to the status of object: “something to be conquered, appropriated, and exploited” ( p.14). This has been the case for morpho butterflies in San José: who are relegated to spaces of scientification and commodification. Demos (2017) suggests that climate change’s main threat is to undo the achievements of modernity. What if we undo those achievements, not my warming the planet but caring for it and all its inhabitants, human and non-human?

3. Insect-action: An exploratory exercise on multi-species becomings.

“If we appreciate the foolishness of human exceptionalism, then we know that becoming is always becoming with –in a contact zone where the outcome, where who is in the world, is at stake.” (Haraway, 2008, 244, original emphasis)

In the last few years, I have been exploring and experimenting with different forms to follow Haraway’s (2016) invitation to “to participate in a kind of genre fiction committed to strengthening ways to propose near futures, possible futures, and implausible but real nows” (p. 136). In this exercise, I did not only wanted to depict the nature/culture divide in the city but use the affordance of the visual to join Escobar (2019) in his quest of “re-earthing of cities.” I pose a simple question: what if we imagine a city where insects can live like in a butterfly garden?

Escobar (2018) suggests that “speculation can act as a catalyst for collectively redefining your relationship to reality, by encouraging-for instance, through what-if scenarios- the imagination of alternative ways of being” (p.17). I engaged in a series of photography interventions as a speculative exercise. Peck (2016) indicates that “in the context of art and ecology, photography is usually seen as a tool for witnessing the changes to our planet, environment and weather systems, but is less of a tool in proposing a vision for the future.” However, drawing on the work of photographer Richard Misrach and Kate Orff (2014), the author demonstrates that digitally intervening photographs can not only depict what it was but what it could be.

Inspired by the activist technique of “culture jamming,” I proceed to manually intervene one of the postcards that appeared in the photo I called “Victorian Dreams.” According to Jordan (2012, quoted in Lekakis, 2017, p. 311), culture jamming is “an attempt to reverse and transgress the meaning of cultural codes whose primary aim is to persuade us to buy something or be someone” (p. 311). And in this case, I would add: relate to others, humans, and non-humans. Using threads, I attempted to show the entanglements between the different “actants” in the postcard. Following Escobar (2019), I tried to depict “the radical interdependence of everything that exists, the indubitable fact that everything exists because everything else does, that nothing preexists the relations that constitute it” (p.132).

Experiment 1: “Insect Jamming”

I would like to keep exploring using threads “to reverse and transgress the meaning” of the photos that are part of my photo essay, as it was my original intention. The fact that I experience several materials constraints caused me some distress but also reminded me that:

“[T]aking fabulation seriously entails proposing possible worlds, inhabiting them with different sorts of work practices, or disciplinary skills, or whatever. Such proposals are not made up. It is a speculative proposal, a ‘what-if.’ It is a practice of imagination, as a deliberate and cultivated practice.” (Haraway in Haraway et al., 2015, pp. 20-21)

And what matters might be not the result but the engagement in a different process of imagination.

Conclusion

This small photo essay that emerged out of a series of photo walks shows how modernist nature/culture dualism is very much alive in the city of San José. Inspired by decolonial and multi-species literature, the essay intends to demonstrate how morpho butterflies are either alienated or commoditized in the city. Ultimately, the photo essay allowed me to creatively explore how morpho butterflies are “the stuff of dreams and nightmares” and “the stuff of economy and culture” (Raffles, 2010, p. 3) in San José.

Photographing the liminality, scientification, and commodification of urban green spaces helped me unsettle “dominant spatial relations of power and injustice” (Gandy, 2011, quoted in Houston et al., p. 196) between humans and non-humans. But also show what is possible. For instance, it permitted me to show the tension between “sensorial extravaganza” and the “victorian science” legacy of the butterfly garden at the National Museum of Costa Rica. While such relations are easy to problematize, it is essential to remember that butterfly gardens can act as “multi-species publics” (Hartingan, 2015). Those spaces can also align humans and non-humans in relations of care (Hartingan, 2015) and have great potential as sites for “ecological learning” (Neves, 2009).

The use of photography also enabled me to propose a visual intervention based on multi-species becomings. By intervening a postcard, following the activist technique of “culture jamming”, I attempted to demonstrate how the visual affords a path to re-imagine human and more-than-human relations and propose alternative futures. The exercise remains exploratory, but it is opening up exciting avenues to keep speculating and re-imagining other (multi-species) ways of “being, doing and knowing” (Escobar, 2018) in the city.

Finally, I would like to point out that while it is easy “to fall in love” with a morpho butterfly and try to relate differently with them, to engage in a more-than-human city logic (Franklin, 2018), we also have to consider the difficulties of caring for “unloved others” (Ginn et al., 2014). During my walks, I kept asking myself: what about “making kin” (Haraway, 2016) with cockroaches or other “unpleasant” insects that also cohabit the city? Those are questions worth asking for future inquires into insects as urban companion species.

References

Archambault, J. S. 2016. Taking love seriously in human-plant relations in Mozambique: Toward an anthropology of affective encounters. Cultural Anthropology. 31(2), pp. 244-271.

Boudreault-Fournier, A. 2017. Recording and Editing. In: Elliott, D. and Culhane, D. (eds). A Different Kind of Ethnography: Imaginative Practices and Creative Methodologies. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 69-90.

Demos, T.J. 2017. Against the Anthtopocene, Visual Culture and Environment Today. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Elliott, D. and Culhane, D. (eds). 2017. A Different Kind of Ethnography: Imaginative Practices and Creative Methodologies. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Escobar, A. 2019. Habitability and design: Radical interdependence and the re-earthing of cities. Geoforum. 101, pp. 132-140.

Escobar, A. 2018. Designs for the Pluriverse. Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Franklin, A. 2017. The more-than-human city. The Sociological Review. 65(2), pp. 202-217.

Gibson, K., Rose, D. B., & Fincher, R. 2015. Manifesto for Living in the Anthropocene. Brooklin: punctum books.

Ginn, F., Beisel, U., & Barua, M. 2014. Flourishing with awkward creatures: Togetherness, vulnerability, killing. Environmental Humanities, 4(1), pp. 113-123.

Haraway, D. 2016. Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham and Londo: Duke University Press.

Haraway, D. J. 2008. When species meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Haraway, D., Ishikawa, N., Gilbert, S. F., Olwig, K., Tsing, A. L., & Bubandt, N. (2016). Anthropologists are talking–about the Anthropocene. Ethnos, 81(3), 535-564.

Hartigan, J. 2015. Plant publics: Multispecies relating in Spanish botanical gardens. Anthropological Quarterly. 88(2), pp. 481-507.

Houston, D., Hillier, J., MacCallum, D., Steele, W., & Byrne, J. 2018. Make kin, not cities! Multispecies entanglements and ‘becoming-world’in planning theory. Planning Theory. 17(2), pp. 190-212.

Jukofsky, D. 2002. Encyclopedia of rainforests. Westport: Oryx Press.

Kirksey, S. E., & Helmreich, S. 2010. The emergence of multispecies ethnography. Cultural anthropology, 25(4), pp. 545-576.

Kohn, E. 2013. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lekakis, E. J. 2017. Culture jamming and Brandalism for the environment: The logic of appropriation. Popular Communication. 15(4), pp. 311-327.

Maleku EM. 2015. Maleku EM fan-page. [Facebook]. [Accessed May 3, 2021]. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/davidmaleku

Misrach, R. and Orff, K. 2014. Petrochemical America. N ew York: Aperture.

Moretti, C. 2017. Walking. In: Elliott, D. and Culhane, D. (eds). A Different Kind of Ethnography: Imaginative Practices and Creative Methodologies. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 91-112.

Neves, K. 2009. Urban botanical gardens and the aesthetics of ecological learning: A theoretical discussion and preliminary insights from Montreal’s Botanical Garden. Anthropologica. 51, pp. 145-157.

Peck, J. 2016. Vibrant Photography: Photographs, actants and political ecology. Photographies. 9(1), pp. 71-89.

Raffles, H. (2010). Insectopedia. New York: Pantheon Books.

Raffles, H. 2001. The uses of butterflies. American Ethnologist, 28(3), pp. 513-548.

Rainforest Alliance. 2012. Blue Morpho Butterflies. [Online]. [Accessed May 3, 2021]. Available from: https://www.rainforest-alliance.org/species/blue-morpho-butterfly

Tsing, A. L., Deger, J., Keleman Saxena, A., & Zhou, F. 2020. Feral atlas: the more-than-human Anthropocene. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Tsing, A. 2010. Arts of inclusion, or how to love a mushroom. Manoa. 22(2), pp. 191-203.

van Dooren. Forthcoming. The Disappearing Snails of Hawai’i: Storytelling for a Time of Extinctions. In: van Dooren, T. And Chrulew, M. eds. Kin: Thinking with Deborah Bird Rose. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Ware. 2011. Earth Now, American Photographers and the Environment. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press.